Pivots are rarely pivots.

I know mine with Wine List certainly wasn’t – it was a nudge on the steering wheel, it was a matter of degrees.

But Seb Evans and Jonny Inglis really did pivot. Today is an interview with Seb, and the story of one of the most successful pivots I’ve seen.

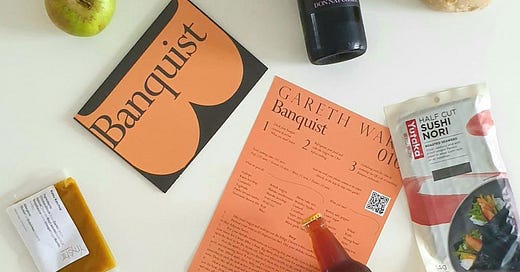

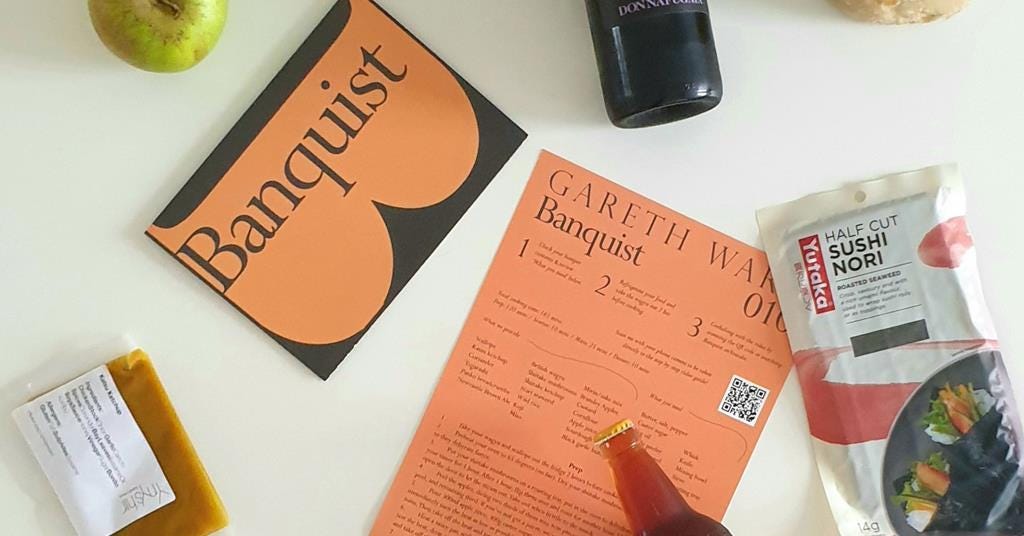

Back in covid times, they were running a restaurant-quality meal delivery service called Banquist. But as the world returned to normal, they recognised the need for a change in strategy. Winedrops was the outcome of that.

Now, let me tell you right off the bat, wine businesses are hard.

Margins are terrible.

Your bricks and mortar wine shop will be making 20-30% on every single bottle sale. Moving that online is difficult when you consider how wine breaks a lot, customers except deals on postage, and shipment costs here is very high.

To make any serious money at all you really need to import wine yourself. At that stage, your margins might get closer to 40-60% if you’re lucky. But again, selling online and that’s gonna go down. And to say nothing off the wines where you can get that margin are usually at the higher end, where the market for them is much smaller.

I say all of this to put into context what a fantastic job Seb and Jonny have done.

Winedrops are in my book one of the UK’s biggest wine success stories. Here’s a few headlines:

25,000 paying members

60-70k bottles sold every month

Profitable unit economics from a very early point

Spending over £200/month on ads, more than tripling volume over a six month period

All this from two entrepreneurs who tried launching their food business at the start of 2020.

I got to know Seb back in the Banquist days when I was running Wine List and we were one of the first importers to sell wine to them. How times changes! And how happy I am for them both.

A huge thanks to Seb for taking part in this interview.

Would you like to start by talking about the Banquist part of your journey?

Two and a half years after leaving uni, I quit my consulting job to start a business with Jonny (Inglis), my business partner. This was just before COVID. Our plans were thrown out of the window when the pandemic changed the entire landscape overnight. This is where we started Banquist. The idea was that, as restaurants were closed, people wanted a restaurant-like experience at home, and there was probably a gap for a more premium version of HelloFresh, Gousto, or Mindful Chef.

At the time, we didn’t really know what we were doing. We were quite lucky that Jonny knew a Michelin-star chef who worked with us on our first menu. We built a waiting list of a few thousand email addresses, and we dropped the first menu out a couple of weeks into lockdown. People would pre-buy the menu and it would be delivered to them on a Friday or Saturday. It sold out straight away.

The business soon developed into a food and wine platform where we’d work with chefs who’d come up with a menu, and we’d pair it with a wine. We were at the more premium end of the spectrum, closer to a restaurant meal price point and experience.

“Within six months, the business was doing £200k a month”

We started just by running lead ads. We were always building the mailing list, largely because we didn’t really know what we were doing in terms of acquiring customers on a continuous basis and also because the product suited that approach. There was a new menu every week, so it made sense to build a list, drop the menu, sell out, and do it all again.

This drop mechanic works really well when there’s genuine scarcity. But if you don’t sell out quickly for a few weeks, the customer quickly learns that there isn’t any real scarcity and the proposition’s appeal starts to decline. So, four or five months in, we realised we’d have to run it more like an e-comm store – we’d take online bookings, and customers could choose which day they wanted the product delivered.

Within about six months the business was doing about £200k a month. We didn't expect it to grow that fast. But the business was flawed, it had so many issues.

Food is a pretty low-margin business, even at the price point we were selling at. Worse, because we didn’t have a consistent product, our gross margin could fluctuate anywhere between 40 and 60%. We’d try and make up a bit of that margin on add-ons like wine and Champagne, but the margins there are tightly capped – even on the decent markup we were taking.

And it was a nightmare logistically. Every box we sent out contained over 100 SKUs. There was no automation in the picking line: we had loads of trestle tables laid out in a warehouse, with pickers picking from each bin. Obviously, things got missed, and customers would get mad.

There’d be loads of wastage, too. Boxes would be left in someone’s garden, and the food would go off. There were huge issues on the delivery side. We originally only delivered within the M25, and we used a refrigerated van network. But they’d also started during COVID, and they were a shambles. There was no tracking, so customers had to wait in all day for a box that may not arrive. So we went to DPD, which could deliver UK-wide. But we still had issues: we needed cool and insulated boxes. It’s a disaster when the weather’s hot because food can go off.

Our revenue peaked in February 2021, in line with Valentine’s Day during the height of lockdown. However, our CACs went up significantly coming out of that period. We were still just about break-even on first purchase and scaling hard. But around March, we started to see our revenue slide. Our revenue graph aligned perfectly with the number of COVID cases, spiking in February and declining from there. Fortunately, we’d raised a seed round about that time; if we hadn’t, we’d probably have run out of money.

By mid-2021, our rounds had closed, and our repeat rate had halved, from the average customer repeating three times a year to 1.4. And our CACs had almost doubled in that period. This was just as restaurants were reopening; Eat Out to Help Out had just launched.

Over the summer, we thought that, at best, we might just pay back the CACs over a customer’s lifetime. If we looked at a five-year horizon, we might make a bit of money, but that was at a really low scale. I couldn't see any way to grow it organically. Customer feedback was consistent – “we love your product, we just don’t have the time to use it any more” or “now that restaurants have reopened, we’ll probably only use you for special occasions.”

It was a classic case of having the best product – our NPS was around 60 – but if the market isn’t there, you can’t get the business to grow.

In Q4 2021, we realised that if we continued on this trajectory, we’d run out of money in the next 12 to 18 months. It was tough, but we didn’t think it was a viable business going forward. We'd kept the team lean throughout - we were aware there was a good chance the fundamentals of the business might change as we came out of COVID. We had three or four people in the office, and we had pickers and packers in the warehouse. But we had to let go of almost everyone else, stripping the team back to the bare bones so we could start thinking about pivots.

We also had to manage investors who’d thought they’d invested in a growing business. Six months later, we had to tell them it wasn’t going well, and that we needed to change the business plan dramatically or we’d run out of money. It was a super stressful period.

How would you recommend to have those investor conversations if this was to happen to someone else?

Some will react very differently to others - it depends on your relationship with the investor. An investor’s experience will also make a huge difference to how important you are in their portfolio. If you’re a big investment in a small portfolio, it’ll be a tough conversation. But if you've taken a £5 million investment from a huge firm, they literally won't care.

As you’re in the business all day every day, step one is making them comfortable with the idea that it isn’t working – your CACs have spiked, retentions are down, and revenue's declining. You need to convince them you can’t carry on this path. They may never accept this point of view, of course. But, depending on how much of the business you own, and how many board seats you have, you can force the issue.

Once they’re comfortable with the idea that the business can’t carry on as it is, there’s a conversation to be had about what you’re going to do with it. Your options are to either shut it down and return the cash, or pivot. Your investor may lean strongly toward the former. Depending on the structure of your shareholder agreement, you can push back and say there’s a good chance you can pivot the business into something new. It then all depends on the investor.

We laid out our plan in broad strokes – the areas we’d test pivoting to, and our success criteria. Ultimately, we were laying out why we weren’t going to do this indefinitely, saying what had or hadn’t worked, and which areas we were going to check against. It's a good idea to run this by the investors to make sure they’re comfortable with it.

Finally, make sure all the legals are in place. We spoke to our law firm relatively early and established our legal rights regarding changing the business plan so significantly. Also, you need to consider the consequences if it all goes tits up.

It sounds simple, but it’s a grim situation. You’re under a lot of stress because you think the business is failing. And you’re having to manage some delicate conversations. Some investors will react well, others can be difficult during this period. You have to be very careful.

So how did you go about pivoting?

We laid out a number of different things we were going to test. Some of them were related to what we were doing – cookware made sense because we had connections with chefs, for instance. There were about six or seven categories altogether, with several ideas in each. We set up Shopify stores for various items and did CAC testing for each category. Did the unit economics make sense? Was there enough gross profit? Was it a viable business?

At the time, Gary V was taking about how well Wine Texts was going. WhatsApp seemed like an easy mechanism to lift and shift that idea. So we started sending wine deals to some of our customers from the old business. We quickly realised that wine is a grey market. With most other commodities, the prices you’re offered on the market are within a very close band. With wine, though, different sellers will sell the same bottle at a 30 to 40% difference.

Because they were sold at such inflated prices, we could sell some of these wines far cheaper than other people. We’d send a deal on WhatsApp, and a team of VAs would look at the replies for the orders. Customers’ credit card information was stored in the back-end, so we could bill them directly. Customers engaged with it. We were doing incredible amounts of revenue very quickly, just from our previous customer base.

“We had four or five phones with several backups and were sending an obscene number of messages a day”

But we realised we needed to work out how we’d grow the business. Before discounting, the margins in wine are already slim. And there needed to be a way to acquire new customers. To grow the business, I said we’d need a good chunk of gross profit right off the bat. That’s where we introduced the annual membership fee. £30 would get you on the list to receive deals. Since then, we’ve increased our prices. It’s developed into a Costco model –£90 a year to join Winedrops for access to the deals and to shop with us.

We grew the WhatsApp channel to a few thousand members. We were sending an obscene number of messages a day but, because we weren’t allowed on the API, we had to use four or five phones with several backups. We had an automation that sat over WhatsApp Web and send all the deals out. That's quite a grey area, so we'd regularly be banned from WhatsApp. We’d lose a day’s orders and would frantically text the people we thought had ordered. It was ridiculous, we couldn’t keep running like that.

So, a year after starting the business, we began developing an app that would send daily push notifications and store customers' card details in the back-end, so they’d be charged automatically every time there was a new deal.

During that time, we were purely WhatsApp. We acquired customers largely through Facebook ads and, weirdly, through lead ads. You'd see the ad, go to a landing page, submit your name and phone number, and join the waiting list. After five days, you’d get a link to join. Bizarrely, it always outperformed just sending someone from an ad to a landing page where they could sign up immediately. I guess it’s about scarcity or exclusiveness.

We introduced a phone sales team, too. We’d run lead ads – you’d get a call from the sales team, and they’d sell you the membership there and then. If you didn’t pick up, you got an email and SMS after three days. But we had the same issue. At some point, it becomes hard to scale purely lead ads. Balancing your lead numbers with how many sales reps you’ve got is tricky–you’re effectively doubling the number of variables in your CACs and trying to keep them all stable at the same time. We decided we couldn’t be purely reliant on lead ads, as it wasn’t scalable.

That all changed, though, when we launched the app.

What was your level of spend on Meta?

When it launched in August 2023, we were probably spending about £60 to £70k a month on lead ads, rising to about £90k by the end of the year. Since February, when we started the app funnel - sending people directly to the app to sign up – our Meta spend is now more like £220k a month.

The overall CAC now gets attributed to Meta, where it was previously split between Meta and the sales team. It’s not apples to apples, but we found it much easier to scale than with a sales team – and the unit economics were better. We’ve been able to scale up pretty aggressively. Now the business has high-level metrics – we’ve got about 25,000 paying members on a variety of plans, with the majority on £90 a year, and we sell between 60 and 70,000 bottles a month. It’s going pretty well.

Part of this is by design, and part of it by luck. We had a model you could apply a membership to, and we’ve been lucky to have £75 after VAT of gross profit to play with on customer acquisition. If we didn’t have that, we couldn’t grow a wine business.

Compare our customer acquisition economics to other wine businesses. They run Facebook ads – typically 'get 60% off your first case'. They pay the CAC to Meta, then they make a loss on that first case of about £20. Overall, their CAC is around £100. It would take years to pay that back.

We run an ad and have a CAC of £X. But we pay back £75 of gross profit and membership after the free trial ends. We have a nice symmetry between what’s good for us and what’s good for the customer. Ultimately, the majority of a customer's LTV comes from membership fees. Even though we make such a slim margin on the wine, we can give the customer cheap deals and it doesn’t really matter.

Unless you’re selling super high-end wine, £90 of LTV across a year is very good. And the membership model works well from an acquisition perspective. It’s quite predictable – you know how retention rates will look because it’s similar to a subscription business. Because you’ve got annual plans, you have to wait a while before you see the impact of any initiatives you’re running, but that compounds over time. The older cohorts are more sticky, you get fewer cancellations, and you get a compounding base of paying members over a longer period.

At that many bottles per month, you must be one of the biggest retailers in the UK?

The UK’s wine market is really fragmented. There are some massive players like Laithwaites, Majestic, and Naked. There’s a huge gap before you get to us and some other smaller players, then another gap before some wine stores and small subscription offerings. We've crossed the initial chasm – getting past the initial step of having enough volume to be competitive on the SKUs we sell and importing at a decent enough volume to make sense.

What’s a typical wine that’s selling well right now?

20% of our SKUs are well known – Whispering Angel, some of the bigger house Champagnes, Bordeaux, and the like. And about 80% are less well known; there might be only a couple of sellers in the UK – we might even be exclusive.

We’ve had to accept that the majority of the volume still goes through the big brands. To demonstrate value, we’re always going to have to sell the brands they’re most looking for – like Whispering Angel, Moet, Bollinger, or Taittinger.

Our best seller has always been Whispering Angel and probably will be for a while. It’s a behemoth in the wine world in terms of appeal.

What is your Vivino sourcing hack?

We have an unusual sourcing method. You get baffled looks when you tell people you don’t taste any of the wines you sell. Instead, if customers are asking for more Provence rosé, we’ll scrape all the SKUs listed on the Vivino Provence region page. Vivino also has a producer page; we’ll try and scrape all the producers’ contact details and import them into a spreadsheet. We have the wine name, the star ratings, the producer’s name and – hopefully – their contact details. Then we can have a mass outreach across 500 or more producers.

‘We don’t taste any the wines we sell’

Early on, when we weren’t working with any producers directly, we’d do a mass introductory outreach to 30,000 winemakers. This caused beef with some of the importers we were working with – the wine industry works on exclusivity agreements. As soon as we sent an email, we’d get phone calls and emails from angry importers. Also, a lot of our advertising said how you’re getting ripped off. We’ve toned it down a bit, but people in the wine industry didn’t like it.

It’s definitely a close-knit community, but we've probably got better at integrating ourselves.

What’s something that didn’t work?

There are so many. Referrals are a waste of time, particularly for a product like ours. Trying to gamify it with ‘give a bottle, get a bottle’ just doesn’t work. I think half the time it cannibalises the organic referrals that would have happened anyway.

App install campaigns are bad quality, too. You have to go further down the funnel with them to complete the sign-up. We wasted quite a lot of money on those.

We’ve always been targeted on paid, so we haven’t spent that much time faffing about with things that have a chance of not working. You probably shouldn’t get to a place where you’re spending £350k a month on Meta. But in the early days, there’s a real benefit in focusing almost entirely on one channel and making that work for you.

Thank you for this. It’s good to hear how you were focused on making money early on and thinking about the business. And your timing was perfect. You were probably one of the first to pivot in this way. Everyone’s catching up with the idea, and you’re ahead of it.

All I’d say is, if you’re burning loads of cash, you’ll inevitably feel under pressure – I’m going to need more cash and I’m always going to be beholden to investors. If you can get off that, and give yourself optionality, running your business will be much less stressful.