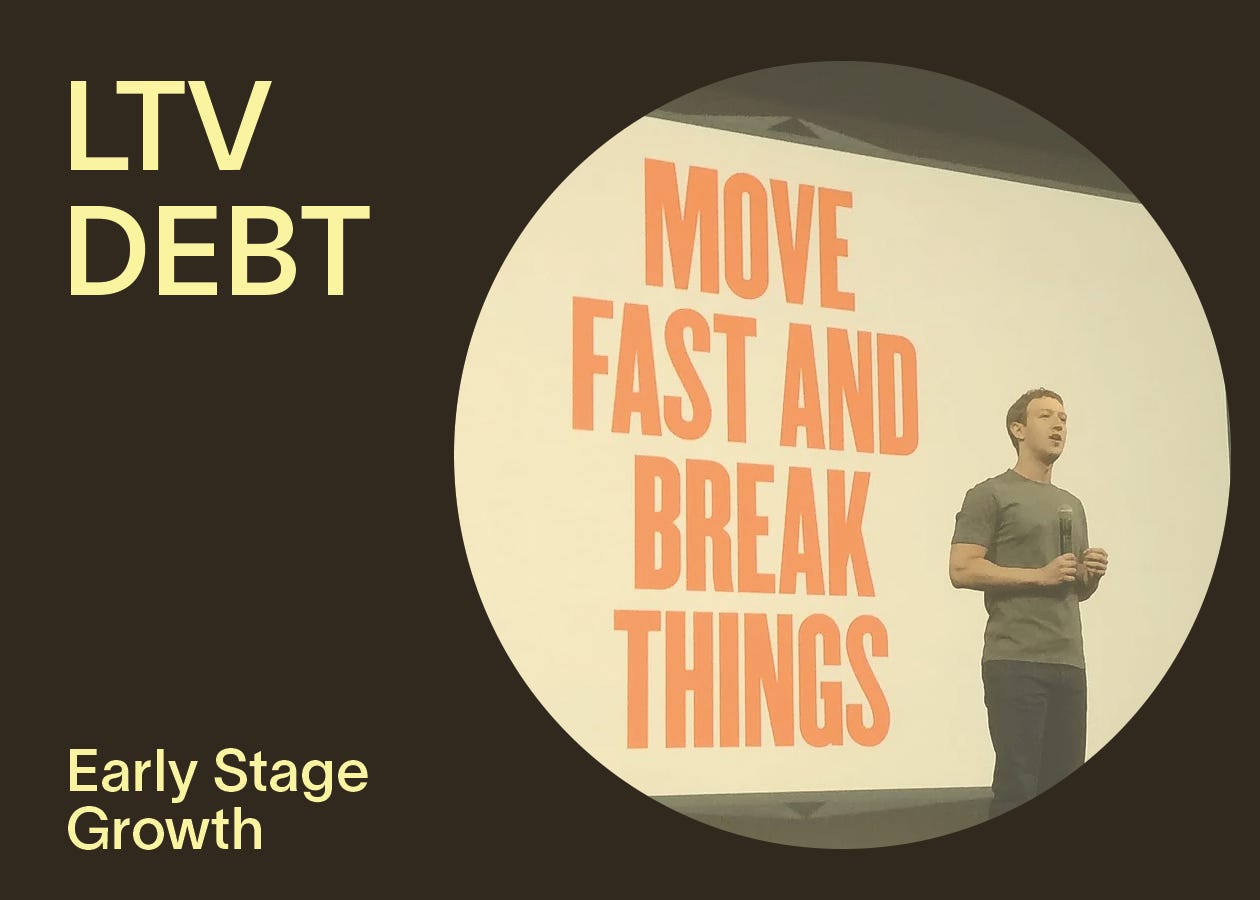

LTV Debt: your growth killer

Why brands hit a wall at £10m ARR (and how the smart ones break through)

Lifetime value debt

I’d like to thank Beth Carter & Daniela Nardelli for help and feedback with these drafts.

I’ve been speaking to lots of CMOs and founders of brands doing £5-20m in revenue. They all describe variations of the same problem: acquisition costs that worked at £50k/month don’t work at £250k/month. Meta is more expensive. Conversion rates dr…